News Details

Nikole Hannah-Jones discusses race, history, and memory with Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice, Annenberg, and Penn Carey Law

Authored by: Juliana Rosati

Photography by: Mark Stehle

Student Life

04/06/23

Growing up in a biracial family in Waterloo, Iowa, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones wondered about the economic differences she noticed between the white relatives on her mother’s side and the Black relatives on her father’s.

“As a young, extremely, painfully nerdy child, I was observing things that probably other kids my age were not,” said Hannah-Jones to a full house in Houston Hall’s Bodek Lounge last week. “I saw how my [white] grandfather worked a blue-collar job and yet had a home and had an acre of land, and my white grandmother never worked outside of the home. And then I see how hard my Black family is working in very difficult jobs in the meat-packing industry. And yet they don’t own their homes and they don’t have any land, and everybody in the house has to work, and they’re still not getting ahead.”

The desire to understand why such disparities existed drove Hannah-Jones to study history and journalism and to learn about discriminatory practices such as the “redlining” of Black neighborhoods by government homeownership programs. Eventually she concluded that “one side of my family was working hard in a country designed to help move them forward, and the other side of my family was working hard in a country designed to hold them back.”

It was one of many manifestations of past injustice in the present that Hannah-Jones discussed during “A Conversation with Nikole Hannah-Jones on The 1619 Project.” The event was presented by Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2) and co-hosted by the Annenberg School for Communication and Penn Carey Law. Moderated by Sierra Club Executive Director Ben Jealous, who holds appointments at all three schools, the event began with an introduction from SP2 Dean Sara S. Bachman.

“As dean of SP2, I am proud of the ways in which we strive to lead with our values,” said Dr. Bachman. “Amidst a polarized national landscape, we are a place that does not shy away from acknowledging and working to dismantle oppression.”

In conversation with Jealous, Hannah-Jones discussed multiple facets of “The 1619 Project,” a groundbreaking initiative of The New York Times Magazine that she began in 2019 and expanded into a #1 New York Times bestselling book in 2021. The book was SP2’s choice this year for the “One Book, One SP2” initiative, which facilitates dialogue across the School about the forces that maintain and perpetuate structural racism and oppression.

With its aim of “placing slavery and its continuing legacy at the center of our national narrative,” the book takes its title from the year that the first enslaved Africans arrived in the colony of Virginia on a ship called the White Lion. That arrival happened the year before the Mayflower landed in Massachusetts.

“Let’s talk about the journey,” said Jealous. “For you, what was driving you to take on such an ambitious task of getting us to rethink our history as a nation?” he asked.

Hannah-Jones recounted how she first learned of the White Lion in high school when a beloved teacher gave her the book “Before the Mayflower” to read. “The title is powerful, because what the title is saying is that every American child learns about the Mayflower in 1620. And yet, the story of the White Lion in 1619 had been completely erased from our national memory,” said Hannah-Jones. “And so even as a 15-year-old, I understood the power of that — that what we are taught to think of as history is in fact, memory, and that memory is manipulated.”

That revelation guided Hannah-Jones’ approach to reframing American history to trace the economic and social impact of slavery from 1619 to the present and to place Black resistance and struggle at the core of the national narrative.

Her research included uncovering the role that Black people played in interpreting the Declaration of Independence and its assertion “that all men are created equal” during the Revolutionary era. “Black people actually read that opening stanza and said, ‘Oh, you can’t — you can’t found a nation with that idea and keep us in slavery. And it’s black people that turn the Declaration into a Liberty document,” Hannah-Jones said.

She cited a chapter of “The 1619 Project” written by Penn Professor Dorothy E. Roberts as one that particularly haunted her through its outlining of the history of race and the regulation of Black women’s bodies. Contemplating the way in which Black women were forced to bear children during slavery, Hannah-Jones wondered, “What is that like, to have to recreate that institution through your bodies?”

Again, parallels of the past appeared in the present. “To this day, Black women no matter our education, no matter our wealth, we’re still most likely to die in childbirth, we’re most likely to see our babies die in childbirth, most likely to have our children taken away from us,” said Hannah-Jones.

Asked by Jealous how she envisions the future of race in America, Hannah-Jones said that while she does not believe we will architect a new society, she does believe we all have the moral obligation to fight for a better world as generations before us have done.

“I could not do what I do if I did not believe we have an obligation — and particularly as a Black woman — we come from people who had to fight for a world they knew they were never going to see, but [who] allowed me to be on the stage with you on this day.”

Reflecting on the public response and backlash to “The 1619 Project” during the question-and-answer portion towards the end of the program, Hannah-Jones said, “What has surprised me the most is how many people want to understand our country better. . . . Large numbers of Americans want the truth, in a way that I wouldn’t have predicted necessarily when I put the project out.”

At the end of the conversation, Jealous thanked Hannah-Jones for her work. “Thank you for your courage. Thank you for your scholarship. Thank you for spending time with us here today,” he said.

SP2 Associate Dean for Inclusion Joretha Bourjolly concluded the discussion. “I want to emphasize that conversations like this one are vital to our School’s mission, and this is a prime example of the kind of necessary dialogue that we continue to encourage in our community,” she said.

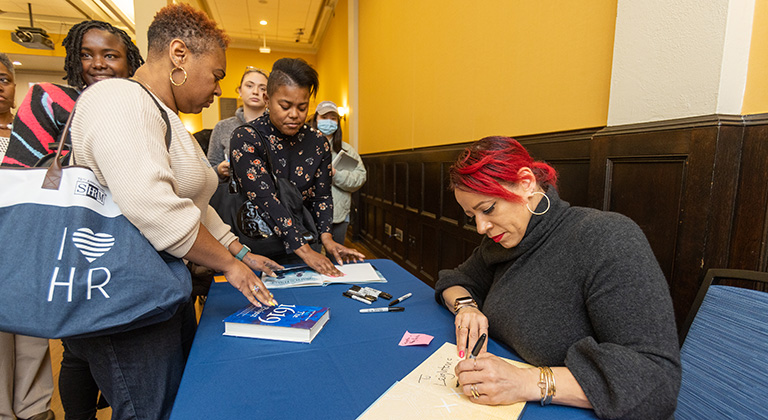

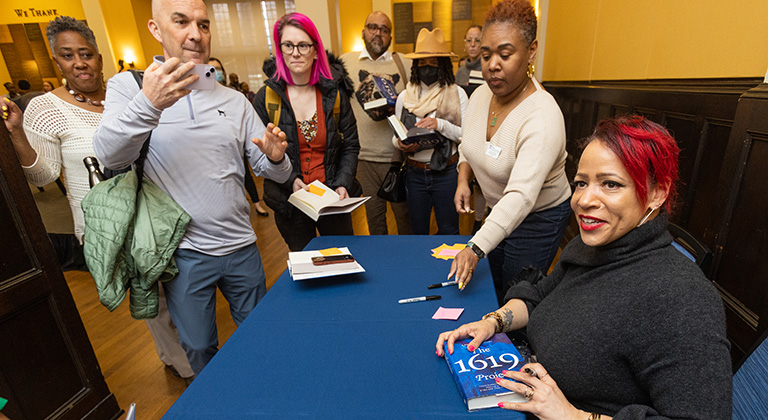

Attendees gathered into a long line for a book signing following the event, and many walked to the tent in SP2’s courtyard behind the Caster Building for a reception with Hannah-Jones.

Nikole Hannah-Jones is the Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of The 1619 Project and a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine. A recipient of numerous awards, including the MacArthur “Genius” Grant, the Knight Award for Public Service, and the Peabody Award, Hannah-Jones is the Knight Chair in Race and Journalism at Howard University.

Ben Jealous, executive director of the Sierra Club, is a professor of practice at the Annenberg School and SP2, and distinguished visiting fellow at Penn Law. He is a former Democratic nominee for governor of Maryland and former national president and CEO of the NAACP.

About SP2

For more than 110 years, the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2) has been a powerful force for good in the world, working towards social justice and social change through research and practice. SP2 contributes to the advancement of more effective, efficient, and humane human services through education, research, and civic engagement. The School offers five top-ranked, highly respected degree programs along with a range of certificate programs and dual degrees. SP2’s transdisciplinary research centers and initiatives — many collaborations with Penn’s other professional schools — yield innovative ideas and better ways to shape policy and service delivery. The passionate pursuit of social innovation, impact, and justice is at the heart of the School’s knowledge-building activities.

People

-

Joretha N. Bourjolly, MSW, PhD

Associate Professor/Clinician Educator

Contact

office: 215.898.5524

fax: 215.573.2099

Email

-

Sara S. Bachman, PhD

Dean

Contact

office: 215.898.5512

fax: 215.573.2099

Email