News Details

Community of Hope: SP2 Associate Professor Secures COVID-19 Crisis Funding to Aid Re-Entering Individuals in Philadelphia

Authored by: Alina Ladyzhensky

Photography by: Naom Keim / The Center for Carceral Communities

Faculty & Research

06/03/20

As efforts to reduce the spread of COVID-19 remain underway in the United States, public health and government officials continue to emphasize the importance of social distancing and avoiding close contact with others. But as experts like Toorjo Ghose, PhD, point out, individuals who are incarcerated—nearly 2.3 million people in America, which has the largest prison population of any nation in the world—are held in facilities where social distancing and basic disease prevention measures are often against the rules, or virtually impossible.

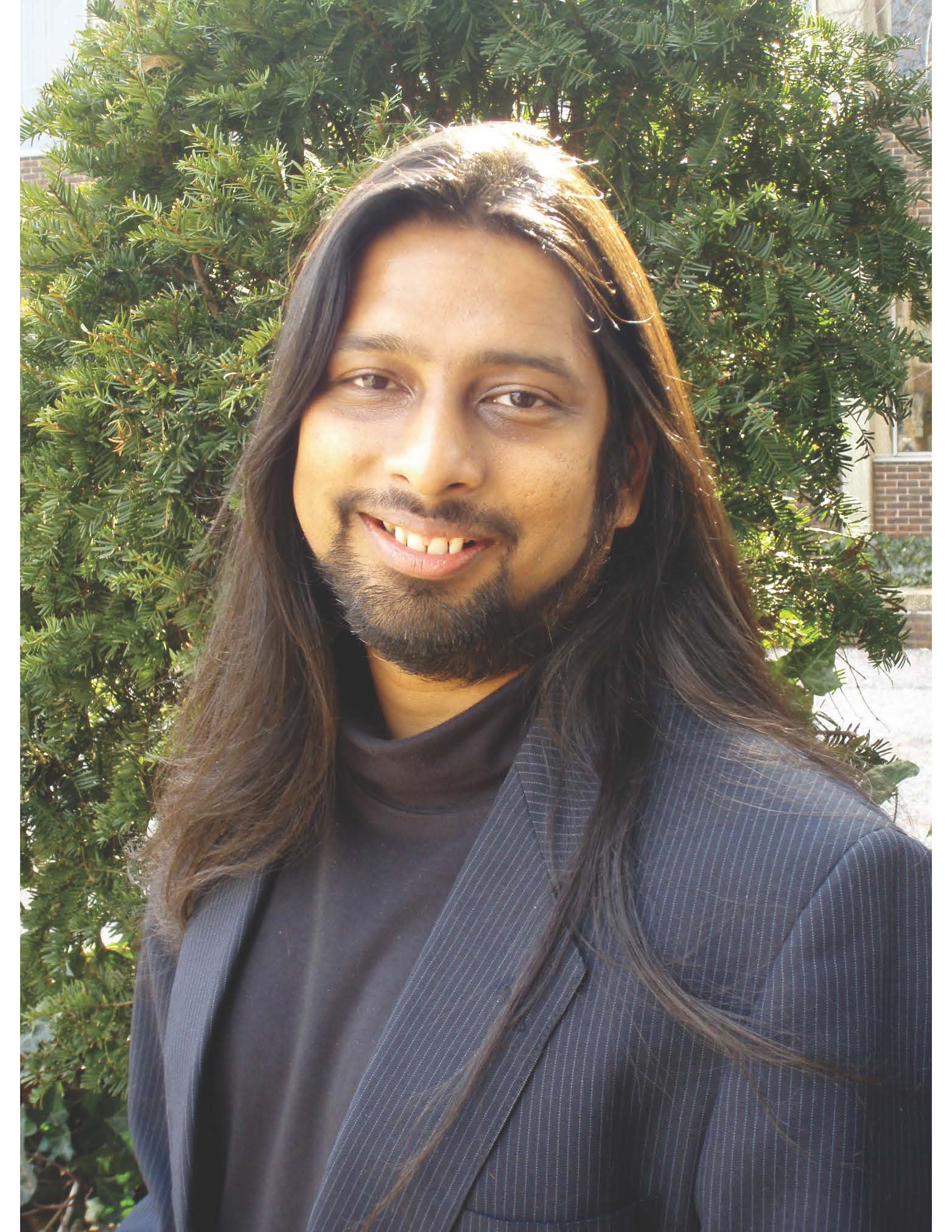

An associate professor at Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2) and CEO of The Center for Carceral Communities, which serves the needs of people being released from incarceration, Ghose’s work intersects in the areas of mass incarceration, criminal justice reform, and social work. Incarcerated people and those who work in correctional and detention facilities, he warns, are at especially high risk of becoming ill and spreading the virus.

“In Philadelphia, we have the largest incarcerated population of any metropolis in the world. In this pandemic, as we’ve found in China and other places, incarcerated populations have sometimes nine or ten times the rates of the epidemic,“ Ghose said. “It’s a survival issue. It’s a human rights issue on a very basic level—the right to live. And of course, there’s the public health angle with the rest of folks, even when they’re not incarcerated. Communities are intimately connected, so anyone getting sick inside means people outside that they’re connected to can also get sick.”

“These are mostly African-American communities or communities of color, sex workers, poor women—all of these communities are at-risk because there’s constant interaction and circulation,” he continued. “For all of these reasons, I think the future of the epidemic here will probably depend on how we work with incarcerated communities.”

Ghose is on the front lines of advocacy for the expedient release of individuals who are incarcerated on nonviolent offenses, bringing awareness to the issue locally and nationally.

“Of the 4,700 people in jail [in Philadelphia] as of January, 70% are black and 18% Latinx. This is a massive group of people of color at extremely high risk of being infected,” he wrote in a recent editorial for the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It will take considerable time for the decreasing number of people entering jails to significantly affect the absolute number incarcerated at this point. In fact, even the pace of seeking the release of those already in jail through the usual petitioning channels might be slowed to a trickle, given the fact that the courts are now virtually shut down.”

According to Ghose, about 100-200 people are now being released from the city’s prison system each week. However, he stressed, release is not a resolution. Within the population of those being released, there is an immense need for services around mental health and substance use disorders, employment, housing insecurity, and more.

A central part of the Center’s mission is connecting individuals with a history of incarceration to such services so they can more safely and successfully re-engage with their families and communities. Ghose and his team rapidly developed a plan to provide those being released with smartphones, enabling providers to replicate services that the Center usually implements with clients.

“Academics are used to sitting down and writing grants over a period of time, and we really did not have time. This is happening even as we speak—people are being released,” Ghose said. “If those folks come out into the shelters or onto the streets without services, the risk of COVID infection from them is high, if they’re not already infected. We know that almost 60-70% of people in jails across the country are testing positive already, and only half are showing symptoms. This is a massive, massive risk.”

Working collaboratively with the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, Ghose and the Center secured several crisis COVID grants, totaling a combined $80,000 in funding from the Ford Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Institute, and the Proteus Fund to cover services, pay for equipment, and track outcomes.

“Six weeks ago, before anyone really thought about it, we prepared to go online entirely because our people are very poor and have lots of challenges coming out of prison. We had to remain connected, and we had to provide services one way or the other. Many social service agencies shut down, but we did not. All of our folks are meeting online through smartphones,” Ghose said. “We’re continuing to engage, and I brought that blueprint to the city. We gave them the blueprint of what we do at the Center, which is CBT [cognitive behavioral therapy], group and peer-oriented engagement around services and mental health, and other types of risk. We worked with the Commissioner of Prisons, who is a social worker, so she fully understood the need of the hour. They’re distributing our phones as folks are getting released, and the phones then become our connection to them, to provide services through the Center.”

While the Center seeks additional funding to continue and expand these efforts, Ghose hopes the intervention work taking place in Philadelphia can become a model for initiatives around the country. Ghose participated in a recent webinar panel discussion on how those reentering society from jails and prisons can avoid homelessness, drawing 700 attendees and, he said, numerous inquiries about how the program he shared could be implemented elsewhere.

As Ghose emphasized, the program is also a way of fostering community and dialogue, allowing vulnerable individuals in carceral communities to help and learn from each other during an unprecedentedly challenging time.

“What we’re doing through the phone program is not just therapy. People come together and share recipes, plans to get married— and on Fridays, we have movie nights through Zoom. It’s forming a community of hope,” Ghose said. “What I’m aware of is that we might be forming a core group of community-oriented peers who are trained in managing the crisis for their communities in Philadelphia. These are the folks who I think will ultimately make a difference as we move forward.”

“That is ultimately where we, as social workers, must take the lead, to collaborate with communities that are going, ‘Hey, we’ve already been here. We know what confinement is.’ We’re actually working with the experts, when we talk about people who are coming out of prison after 20 years inside. They have the strength, and they are the ones who are going to take us forward.”

People

-

Toorjo Ghose, MSW, PhD

Associate Professor

Contact

office: 215.898.5512

fax: 215.573.2099

Email